In the past few decades, there has been a deep discussion about the ideological roots of fascism, and above all, a great misunderstanding about the collectivist principles that this authoritarian movement promulgated. To understand this ideology better, it is necessary to know in depth the life, beliefs, and principles of both its political leaders (such as Benito Mussolini) and its philosophical leaders (such as Giovanni Gentile).

Mussolini was an Italian military man, journalist, and politician who was a member of the Italian Socialist Party for 14 years. In 1910, he was appointed editor of the weekly La Lotta di Classe (The Class Struggle), and the following year he published an essay entitled “The Trentino as seen by a Socialist.” His journalism and political activism led him to prison, but soon after he was released, the Italian Socialist Party—increasingly strong and having achieved an important victory at the Congress of Reggio Emilia—put him in charge of the Milanese newspaper Avanti!

This intense political activism was followed by World War I, which marked a turning point in Mussolini’s life. In the beginning, the leader of the Socialist Party was part of an anti-interventionist movement, which opposed Italy’s participation in World War I. However, he later joined the interventionist group, which earned him expulsion from the Socialist Party.

Mussolini participated in the war and went on to take advantage of the dissatisfaction of the Italian people, due to the few benefits obtained by the Treaty of Versailles. He then blamed his former comrades of the Socialist Party for it, and that is when he started the formation of the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, which later would become the Italian Fascist Party.

Based strongly on the nationalist sentiments that flourished as a result of the combat, Mussolini came to power by the hand of violence, fighting against the traditional socialists and shielding himself in the famous squadron of the black shirts. It was only then that the ideological complex of fascism would begin to take shape.

Who Is the Ideological Father of Fascism?

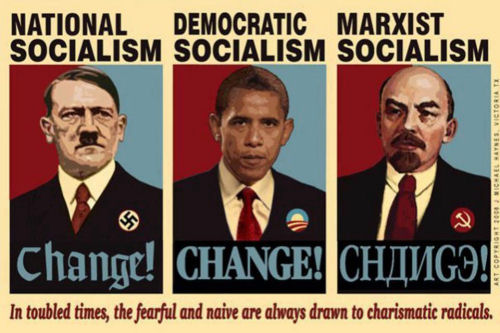

Practically everyone knows that Karl Marx is the ideological father of communism and socialism and that Adam Smith is the father of capitalism and economic liberalism. Do you know, in contrast, who the mind behind fascism is? It’s very likely that you don’t, and I can tell you in advance that the philosopher behind fascism was also an avowed socialist.

Giovanni Gentile, a neo-Hegelian philosopher, was the intellectual author of the “doctrine of fascism,” which he wrote in conjunction with Benito Mussolini. Gentile’s sources of inspiration were thinkers such as Hegel, Nietzsche, and also Karl Marx.

Gentile went so far as to declare “Fascism is a form of socialism, in fact, it is its most viable form.” One of the most common reflections on this is that fascism is itself socialism based on national identity.

Gentile believed that all private action should be oriented to serve society. He was against individualism, for him there was no distinction between private and public interest. In his economic postulates, he defended compulsory state corporatism, wanting to impose an autarkic state (basically the same recipe that Hitler would use years later).

A basic aspect of Gentile’s logic is that liberal democracy was harmful because it was focused on the individual which led to selfishness. He defended “true democracy” in which the individual should be subordinated to the State. In that sense, he promoted planned economies in which it was the government that determined what, how much, and how to produce.

Gentile and another group of philosophers created the myth of socialist nationalism, in which a country well directed by a superior group could subsist without international trade, as long as all individuals submitted to the designs of the government. The aim was to create a corporate state. It must be remembered that Mussolini came from the traditional Italian Socialist Party, but due to the rupture with this traditional Marxist movement, and due to the strong nationalist sentiment that prevailed at the time, the bases for creating the new “nationalist socialism,” which they called fascism, were overturned.

Fascism nationalized the arms industry, however, unlike traditional socialism, it did not consider that the state should own all the means of production, but more that it should dominate them. The owners of industries could “keep” their businesses, as long as they served the directives of the state. These business owners were supervised by public officials and paid high taxes. Essentially, “private property” was no longer a thing. It also established the tax on capital, the confiscation of goods of religious congregations and the abolition of episcopal rents. Statism was the key to everything, thanks to the nationalist and collectivist discourse, all the efforts of the citizens had to be in favor of the State.

Fascism: the Antithesis of Liberalism & Capitalism

Fascism claimed to oppose liberal capitalism, but also international socialism, hence the concept of a “third way,” the same position that would be held by Argentine Peronism years later. This opposition to international socialism and communism is precisely what has caused so much confusion in the ideological location of fascism, Nazism, and also Peronism. Having opposed the traditional internationalist Marxist left, these were attributed to the current of ultra-right movements, when the truth is that, as has been demonstrated, their centralized economic policies obeyed collectivist and socialist principles, openly opposing capitalism and the free market, favoring nationalism and autarchy.

In that sense, as established by the philosopher creator of fascist ideology, Giovanni Gentile, fascism is another form of socialism, ergo, it was not a battle of left against right, but a struggle between different left-wing ideologies, an internationalist and a nationalist one.

In fact, in 1943, Benito Mussolini promoted the “socialization of the economy,” also known as fascist socialization; for this process Mussolini sought the advice of the founder of the Italian Communist Party, Nicola Bombacci; the communist was the main intellectual author of the “Verona Manifesto,” the historical declaration with which fascism promoted this process of economic “socialization” to deepen anti-capitalism and autarchism, and in which Italy became known as the “Italian Social Republic.”

On April 22, 1945 in Milan, the Fascist leader would declare the following:

“Our programs are definitely equal to our revolutionary ideas and they belong to what in democratic regime is called “left”; our institutions are a direct result of our programs and our ideal is the Labor State. In this case there can be no doubt: we are the working class in struggle for life and death, against capitalism. We are the revolutionaries in search of a new order. If this is so, to invoke help from the bourgeoisie by waving the red peril is an absurdity. The real scarecrow, the real danger, the threat against which we fight relentlessly, comes from the right. It is not at all in our interest to have the capitalist bourgeoisie as an ally against the threat of the red peril, even at best it would be an unfaithful ally, which is trying to make us serve its ends, as it has done more than once with some success. I will spare words as it is totally superfluous. In fact, it is harmful, because it makes us confuse the types of genuine revolutionaries of whatever hue, with the man of reaction who sometimes uses our very language.”

Six days after these statements, Benito Mussolini would be captured and shot.