Authored by Rusty Guinn via EpsilonTheory.com,

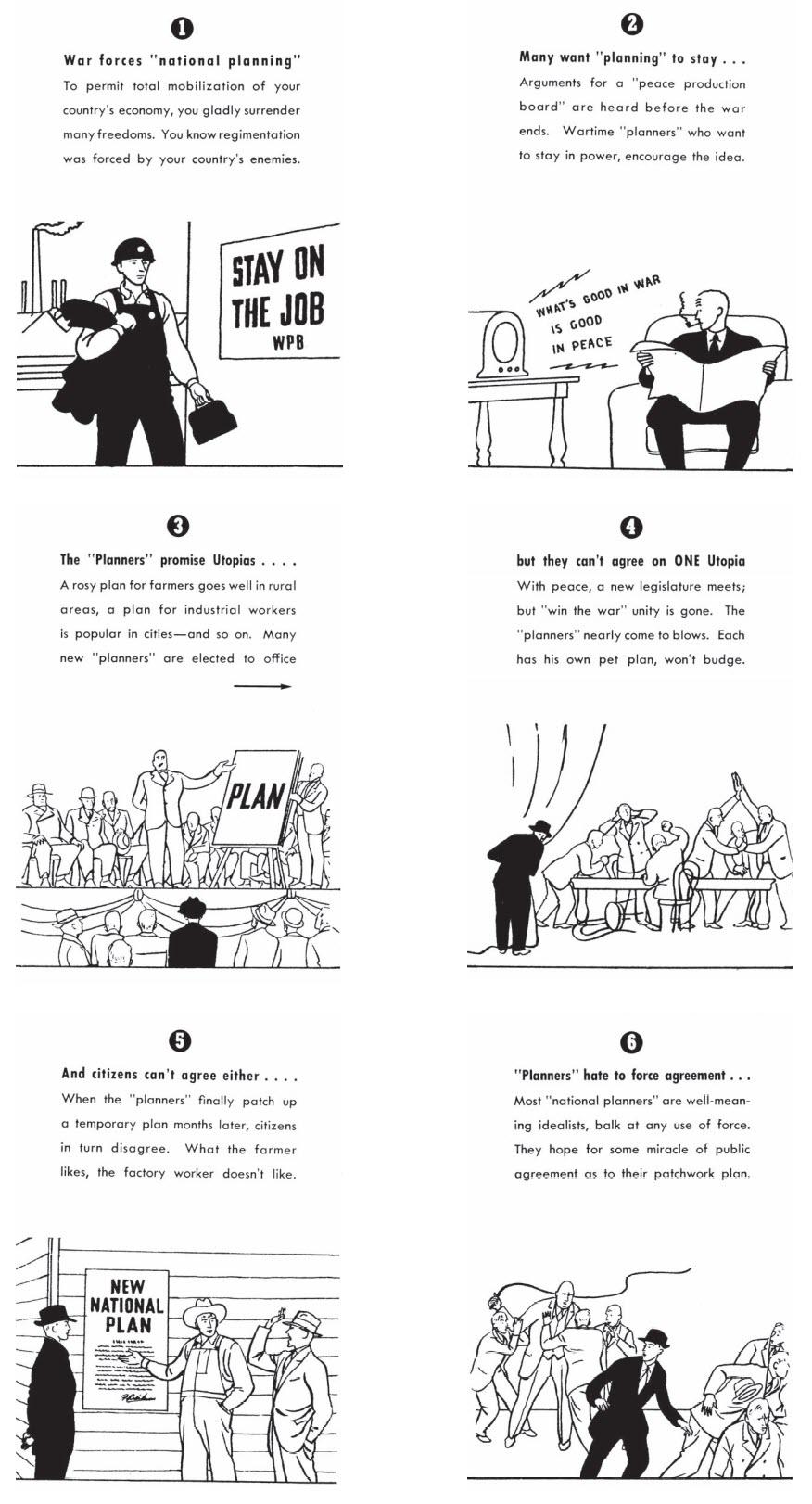

Some years ago, Look, a now-defunct American magazine, published a set of cartoons which attempted to illustrate the basic framework of Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom. We have published them in other essays. We did it here. And here. And…here. Today we do it again with an excerpt of the first ten ‘steps’. You can see the full range on the Mises Institute’s website.

We keep publishing these cartoons because they are relevant and because they are powerful illustrations of the role of narrative in aiding the concentration of political power. We also think it is valuable to frequently consider forces like this which remain so applicable across time and circumstance.

Yet there is more than one path to serfdom. This is one. In the illustrated scenario, a major event like World War II is used by well-meaning political leaders to establish more long-lasting central control over the planning of economies. They also conjure a Strong Man to see them through. It was a familiar story for mid-20th century Europe and many other times in history. There are other paths. For example, there are paths which run through corporate monopoly power or, say, the Church. These sorts of paths tend to get less attention from those of us who cherry-pick when it comes to Hayek, but that doesn’t make them any less real.

Still, the power of the political Strong Man is a special case. The political Strong Man who seized power immorally or illegally is an even more special case. Yet it isn’t so much the specific case study that interests me so much as the evolution of the road itself. And it has evolved. Seventy-five years after the book that described it was printed, the road to serfdom has gotten shorter. Faster. Those who seek power no longer have to grapple with the kind of public debate that arrested the growth of political movements in the past. Always-on traditional and social media now provide much more powerful tools for missionaries to create common knowledge out of whole cloth. The Widening Gyre has created an environment of identity-based political support ready to muster at will. The methods to summon existential memes to compel compliance are now old hat.

In 2020, all it takes is a critical mass of missionaries to take up the message.

There is a new Road to Serfdom, and I think it looks something like this.

Step 1: Missionary promotes the narrative that “something must be done” about a problem

Step 2: Other missionaries work to establish the narrative as common knowledge, something “everybody knows that everybody knows”

Step 3: Missionaries decry lack of action by traditional mechanisms, need for an unfettered hand to pursue it

Step 4: Missionaries make an explicit play for power

Step 5: Missionaries warn what will happen if they are not given the power

No matter your political identity, I suspect you can think of appealing examples of this pattern. But if you will indulge me, I want to walk you through an especially relevant, present-day example. We are going to explore the evolution of the curious intersection of central banking and climate change over the past four years.

We’re going to do it because I think we are charting a potential new route on the road to serfdom.

That road starts in January 2016, with Step 1.

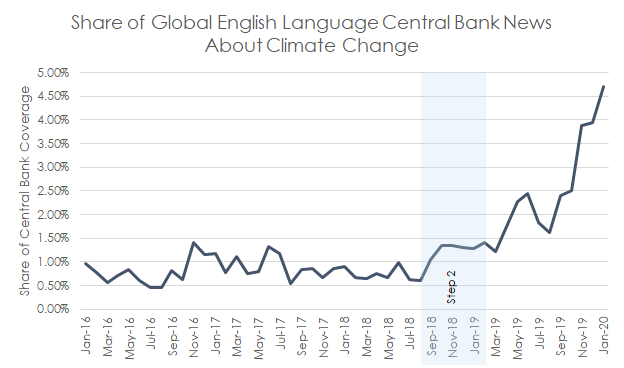

Step 1 | Missionary promotes the narrative that “something must be done” | January 2016 – August 2018

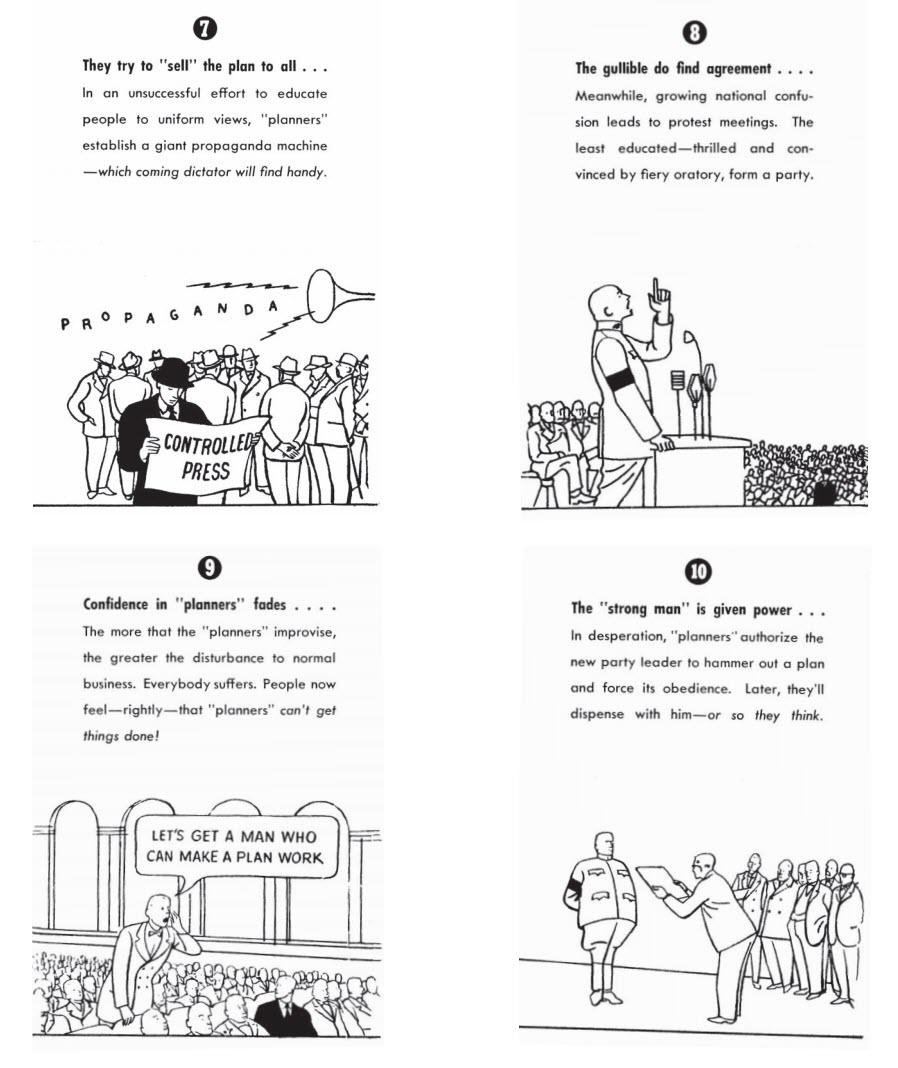

Sources: Epsilon Theory, LexisNexis Newsdesk

The title of this graph is a bit of a mouthful. So what, exactly, does it show? In each month between January 2016 and January 2020, it plots a fraction. The numerator of that fraction is the total number of articles with text referring to both climate change AND central banks, where “central banks” means both the term “central banks” or “central banking” as well as the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, People’s Bank of China and the key public-facing officials of those institutions. The denominator of that fraction is just the raw count of central banking articles.

As you’ll note in the first graph above, the first period we charted runs from approximately January 2016 through August 2018. During this first stretch, there was almost no relationship between the way that elected political leaders, unelected political officials, corporate leaders and media members with prominent platforms (collectively in our parlance, “missionaries”) wrote or spoke about central banks and climate change together. These were practically non-overlapping topics. More specifically, between January 2016 and August 2018 about 8 in every 1,000 news articles about the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, People’s Bank of China, European Central Bank or Bank of England, or any of their respective key officials, related the activities of those banks to climate change.

You will probably also note a period of modest acceleration in the relationship between these topics between November 2016 and the summer of 2017. This was the result of broad economic pieces published in the wake of the election of Donald Trump, many of which discussed, analysed and expressed opinions on a range of topics, from climate and energy policy to the Fed without necessarily connecting the two. Excluding that brief flurry, articles which related the two concepts were almost entirely related to one of two things:

- The PBOC’s establishment of guidelines for the issuance of Green Bonds; and

- Statements made by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chair of the Monetary Policy Committee

I am always inclined to ascribe at least some missionary intent to any publication referencing the PBOC, but these are largely perfunctory, logistical and trade articles. Not speeches, finger-waving or “this is how you should think about the environment” propaganda. Green-washing propaganda? Yes, I think that’s a charge you could level. But while it is a lark to talk about actors buying “clean” jet fuel for their G5s in Davos, or the world’s biggest polluter touting its various green initiatives, that isn’t really what we’re talking about here.

No. Instead, what interests us is Goldman alum Carney, the first mission creep missionary. From a June 2016 article in Canada’s Globe And Mail, he was already active establishing the idea that something must be done to create a connection between regulatory policy – more to the point, monetary policy – and climate change. And he did so in a way that was crafted for an audience of institutional investors.

He estimated that global carbon reduction needs imply “somewhere in the order of $5 to $7-trillion a year” in clean-infrastructure investments. “The question is, how much of that is going to be financed through capital markets?” He said that if there is a “global standard” established for green-infrastructure bonds – something the G20 is working on – it would create “a core mainstream fixed-income opportunity.”

He said that China, in particular, has large needs for such infrastructure that could generate relatively high-yielding investment products.

He also argued that a “a consistent, comparable, reliable” global system for corporate disclosure on carbon emissions would better allow equity markets to price in relative risk into company valuations. Mr. Carney has been championing such a system for much of the past year, in his dual roles as the head of the Bank of England and the chairman of the international Financial Stability Board.

“The relative value opportunity in equities is considerable,” he said.

“Having the Governor of the Bank of England here sends a very strong message that it is important that we act now, and that we have a real opportunity for Canadian business,” Ms. McKenna told reporters following the session.

Source: Climate change a $5-trillion opportunity, Globe and Mail, July 16, 2016

Carney’s September 2016 speech in Berlin was a masterpiece in narrative construction, explicitly conflating climate change with terms of art in the world of financial risk management. He begins:

Your invitation to discuss climate change is a sign of the broadening of the responsibilities of central banks to include financial as well as monetary stability. It also demonstrates the changing nature of international financial diplomacy.

Source: Resolving the Climate Paradox, Mark Carney, September 22, 2016

That is, I believe, what we call saying the quiet part out loud. Still, to really appreciate the skill being applied here, take note of the effective redefinition of climate change in the most well-known memes of financial risk. A Minsky moment, indeed.

A wholesale reassessment of prospects, as climate-related risks are re-evaluated, could destabilise markets, spark a pro-cyclical crystallisation of losses and lead to a persistent tightening of financial conditions: a climate Minsky moment.

Source: Resolving the Climate Paradox, Mark Carney, September 22, 2016

In fairness to Carney, at this point he is not advocating the establishment of some grand global central banker-driven policy-making body. In fact, in the speech he delivered at Lloyd’s London to really kick off this whole cycle back in September 2015, he said explicitly that he doesn’t see that as the proper response. His speeches and plans have favored mostly an expansion of accounting standards for carbon reporting, climate change-based stress testing and application of existing risk management tools to this emerging problem. In short, Carney’s vision was an extension of existing central banking tools for measuring, responding to and mitigating systemic shocks that might be the result of climate change. If you see the $10-dollar term of art ‘macroprudential‘ in this note, that’s what we mean by it.

Still, for months, we had a missionary – or perhaps a prophet – alone in the wilderness, shouting that something must be done to address the risks of climate change through monetary policy.

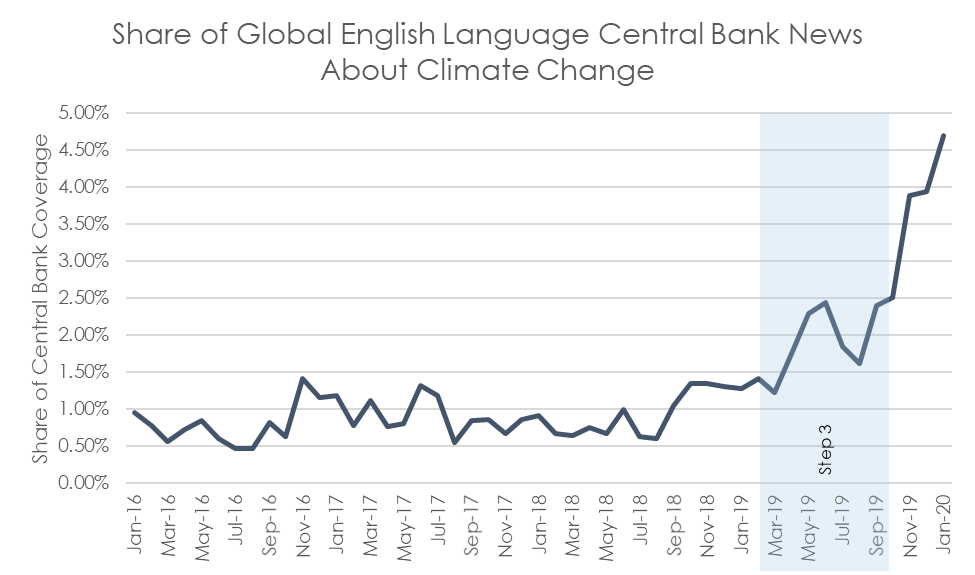

Step 2 | Other missionaries work to establish the narrative as common knowledge, something “everybody knows that everybody knows” | September 2018 – January 2019

Source: Epsilon Theory, LexisNexis Newsdesk

While there were occasional flareups in the discussion over this period – usually prompted by a Carney speech or a related conference topic within the professional environment of economics, it wasn’t until the fourth quarter of 2018 that any acceleration in the intersection of these two topics began. In the build-up to Davos in 2019, other missionaries in the world of economics and economics journalism began to take on the mantle of addressing climate change through financial regulation. Some of the less noteworthy among them clamored already for an unfettered, unelected global power to tackle it.

Here, though, the breakdown in international cooperation and trust becomes really damaging. Ideally, existing global institutions – the IMF, the World Bank, the UN and the World Trade Organization – would be supplemented by a new World Environmental Organisation with the power to levy a carbon tax globally. Even in the absence of a new body, they would be working together to face down the inevitable opposition to change from the fossil fuel lobby.

Source: Larry Elliott, ” Climate change will make the next global crash the worst”, The Guardian, October 11, 2018

There are a lot of ways to write “I want to establish a world body who can tax everyone on the planet, but I’ll settle for some strongly worded letters to the CEO of ExxonMobil,” and this is apparently one of them.

Still, this sort of overzealous shield-banging was the exception during this period, not the rule. The most prominent emerging voices, former officials of the Federal Reserve and some of their associates in the Climate Leadership Council, began a regular flow of Op-Eds to papers and publications around the United States. The flood began in earnest on September 10, 2018 with the publishing of an Op-Ed piece in Fortune written by Janet Yellen and Ted Halstead. The CLC had published its plan almost a year earlier to some acclaim from editorial pages, but had not gotten much traction. This did.

Other economists had similar Op-Eds published in the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Dallas Morning-News and many other large, metropolitan publications in each of October, November and December 2018. Nobody here was pining for the Fed to have ‘managing climate change risks’ added to its mandate. None looked to take the intersection of monetary policy and climate change beyond macroprudential risk management. None that I can detect (other than including Fed officials as authors) even so much as imply a role for central banks. Most contemplate a set of the CLC’s regulatory policies for addressing climate change in context of traditional political systems governed by elected officials. If you ask me (and you didn’t, but you’re on my website), their proposals and Op-Eds were perfectly sensible and blessedly light on existential memetics.

But from a narrative perspective, whether the proposals were sensible, made in earnest and good faith, or even if they were a good idea, simply doesn’t matter. From a narrative perspective, what is important is that these well-intentioned planners established common knowledge that financial regulation would be necessary to mitigate the negative impact of climate change.

By the end of 2018 and 2019, I think that it was something everybody knew that everybody knew.

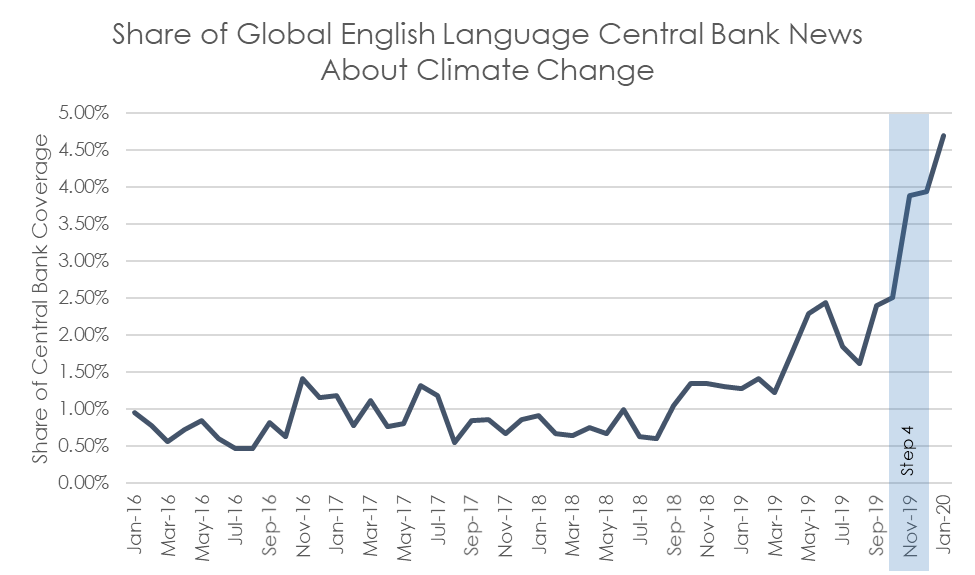

Step 3 | Missionaries decry lack of action by traditional mechanisms, need for an unfettered hand to pursue it | February 2019 – October 2019

Source: Epsilon Theory, LexisNexis Newsdesk

Davos in 2019 was…well, it was like Davos always is. It was an opportunity for political and corporate missionaries to scream from a microphone provided by media missionaries for reasons that escape literally every other person on the planet. Still, as irritating as we might find it, the narratives promoted there often take root.

Four days after Davos concluded, the opening salvo of Step 3 was an open letter submitted by 20 Senate Democrats to Jerome Powell telling him that they considered it “imperative” that the Federal Reserve ensure the stability of the US financial system in the face of climate change risks. The letter was directed by a member of the Banking Committee, and a person whose job is, coincidentally, to make and pass laws which could govern just about every conceivable climate policy.

But it wasn’t just congressional leaders who began to float the idea that an independent institution like the Fed ought to more explicitly incorporate climate change into its mandate. It was the Fed itself. In March, a senior policy adviser at the San Francisco Fed wrote approvingly of the latitude some comparable institutions have to influence the relative cost of capital of “green” vs. “non-green” issuers of securities.

This is a Big Deal.

The question of using a central bank’s balance sheet to influence asset prices was controversial and problematic enough when the activity was largely constrained to government debt. It was more concerning when it began to include corporate debt securities and (in some countries) equity securities. Probably half of the content on this website concerns our agitation with these activities, so I won’t belabor their discussion. I will, however, say that the expansion of central banks’ activities to include the open, intentional and unavoidably arbitrary influencing of costs of capital and securities prices for different sectors and companies to reflect some scheme of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ isn’t just a simple next step. It would represent a quantum change in the accepted macroprudential role we cede to central banks under our present social contract.

I think it is important, especially for those who may not deal with these questions every day, to know what is being suggested here. Some economists were – and are – proposing that an unelected body sit in the position of determining by fiat the price at which (and whether!) different companies would be able to access capital based on that body’s assessment of whether that institution was deemed to be sufficiently green. And yes, some of this is already happening.

In a classic economist’s conclusion, the author then lamented the Fed’s more limited present power.

Many central banks already include climate change in their assessments of future economic and financial risks when setting monetary and financial supervisory policy. For the Fed, the volatility induced by climate change and the efforts to adapt to new conditions and to limit or mitigate climate change are also increasingly relevant considerations. Moreover, economists, including those at central banks, can contribute much more to the research on climate change hazards and the appropriate response of central banks.

Climate Change and the Federal Reserve (March 25, 2019)

By April, some missionaries started saying the quiet part out loud again. In a Fortune article published in April 2019, various commentators presented a cynical step-by-step explanation of the application of the “gameplan” that had worked to get central banks engaged in diversity issues that also had proved too problematic to solve via democratic and political mechanisms.

Now, central banks are making a similar case when to comes to addressing climate change…“If you get in with the herd that says climate change is a financial risk, then central banks have all the tools,” says Williams. “I think what you’re seeing is a wave of progress.”

Central Banks are the World’s New Climate Change Activists (Fortune, April 26, 2019)

All that must be done is to change common knowledge. That is exactly what pieces like this do. They change what everybody knows that everybody knows. By the late spring of 2019, everybody at least suspected that others suspected that climate policy was too important to be left to officials and deliberative bodies constrained by pesky consensus-building and politics.

Major financial news outlets began covering the topic from this angle at this time as well, now bringing up the “M” word. Mandate. It simply means the official policy objective(s) to be targeted by the unelected officials of the world’s various central banks. Bloomberg brought up the topic in early April. And yes, the below is theoretically from a news article, not an Op-Ed, but leave that alone for the moment.

Freak weather events blamed on global warming — largely regarded as temporary shocks so far — risk becoming serious impediments to economic management in the future. They could even require a rethink of central-bank mandates at some point

Central Banks Are Thinking Greener as Climate Change Hits Policy (Bloomberg, April 2, 2019)

The idea that subjective regulatory policy, rather than traditional macroprudential activities, ought to be shifted to an unelected body was now mainstream. The related narrative of the need for a central bank mandate for climate change, which in most cases would codify that shift in responsibilities, was now mainstream.

When narratives begin to accelerate, we find that they often manifest in Fiat News. That’s our term for the the use of affected language, opinions presented as fact and obvious issue framing in news articles. The intent is usually to tell you how to think about an issue. Nobody does it better than the New York Times, and here they really go for the gusto. In the lede, no less! I’ll leave you to guess at the author’s opinion.

A top financial regulator is opening a public effort to highlight the risk that climate change poses to the nation’s financial markets, setting up a clash with a president who has mocked global warming and whose administration has sought to suppress climate science.

Climate Change Poses Major Risks to Financial Markets, Regulator Warns (New York Times, June 11, 2019)

In July, the economics research side of a global investment bank published a piece asserting that not adding climate change to the mandate of central banks could be considered an abrogation of fiduciary duties owed by the Federal Reserve to citizens. They added that even if that wasn’t possible, they might have an argument for considering it part of the mandate already given its theoretical impact on employment and prices. Let us conveniently ignore for a moment that extension of this logic would permit the inclusion of literally every molecule between earth and sun in the mandate of central banks.

The real quiet-part-out-loud moment, however, came later in July. It was a widely circulated and shared piece published in Foreign Policy magazine that was later rehashed in an interview with the Atlantic. It was very explicit about the belief not only in the attractiveness of a mandate change, but in a mandate which went well beyond the macroprudential authority we have traditionally afforded to our central banks.

As of yet, their response is defensive, focusing on managing financial risks. The rest of us have no choice but to hope that they move into a more proactive mode in time.

Why Central Banks Need to Step Up on Global Warming (Foreign Policy, July 20, 2019)

And that is exactly where the narrative starts to take off from what Carney originally had in mind, and from the narrative the various CLC authors promoted in their Op-Ed push of 2018. The author asserts that central banks need to embrace not only the regular roles of ensuring liquidity and functioning lending markets, but the re-engineering of the economy, where it is growing and where it isn’t.

Taken at face value, the macroprudential approach makes sense. It is better for the financial system to be resilient. But in adopting this approach, the central banks are using the same conservative approach to climate change that proved lacking when it came to financial reform. In the years since the 2008 financial crisis, they have perfected their tools of crisis management but without addressing the root cause of the problem: that banks were too big to fail. More than a decade on, they still are.

Of course, everything possible should be done to make the financial system resilient in the face of climate-related Minsky moments. But why is financial stability the principal concern? Central banks and financial regulators should instead be urgently exploring what they can do to alter the course of economic growth so that the world can rapidly decarbonize and thus prevent worst-case climate change—and the related financial fallout—in the first place….

…If the world is to cope with climate change, policymakers will need to pull every lever at their disposal.

Why Central Banks Need to Step Up on Global Warming (Foreign Policy, July 20, 2019)

Or, as the author put it more succinctly in the Atlantic interview:

Realistic? No. I mean, depends what you mean by realism. The scale of the challenge requires a boldness of action for which there is no precedent.

How Climate Change Could Trigger the Next Global Financial Crisis (The Atlantic, August 1, 2019)

Let’s be really clear about what this is: This is a clarion call for unelected individuals participating in a body with limited transparency and limited oversight to be granted the authority to exert policies to lift up specific industries, companies and individuals, and to bring down specific industries, companies and individuals.

This is Step 9 of the Hayek road.

It is also the culmination of Step 3 of our variant of that road. Its call is always Always ALWAYS the same: We are faced with an existential risk! We simply cannot abide the slowness and inefficiency of open democratic processes! We must vest power in a body with the autonomy and authority to act without debate or politics!

Let’s get a man who can make a plan work.

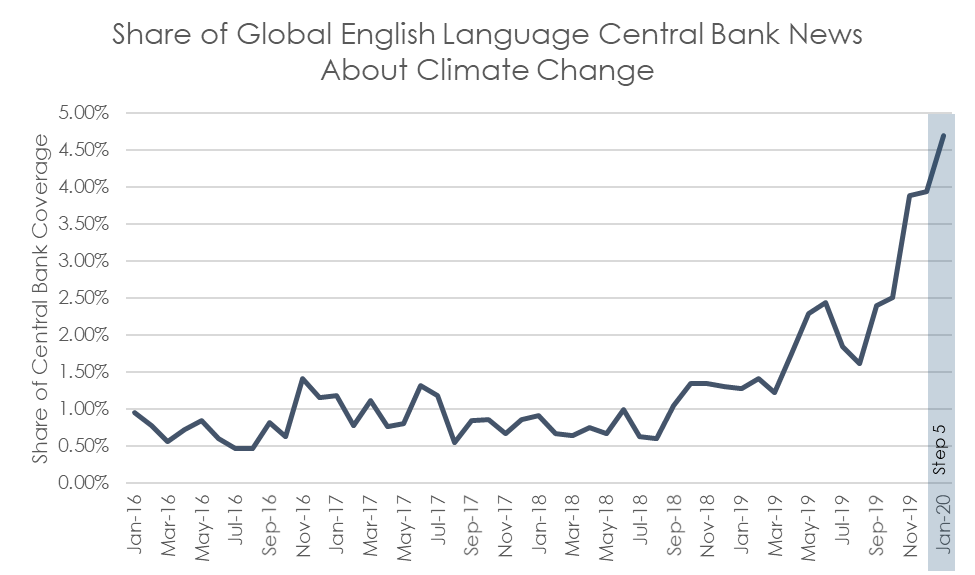

Step 4 | Missionaries make an explicit play for power | November 2019 – December 2019

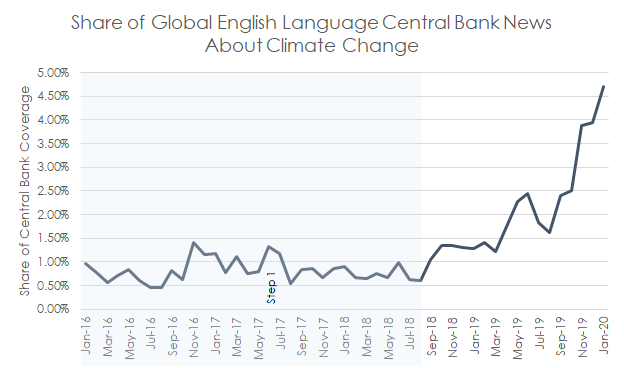

Source: Epsilon Theory, LexisNexis

The demand for “a man who can make a plan work” is only that – a demand – until its call is heard and taken up. Our next brief period is defined by the taking up of that call. Only it wasn’t a man. It was taken up by incoming ECB President Christine Lagarde. She did so at a time that the intersection of these two topics was reaching a fever pitch.

By then, the narrative pivot so cynically described earlier was no longer a secret. What was once “we need to consider stress testing, reporting requirements and accounting standards for climate-related risks to the financial system” had become “we support the ECB as a lever for climate protection.”

Not just protecting the financial system from unique risks that might be presented by climate change. Protecting the climate. I am not paraphrasing.

“We will support Lagarde as she makes the E.C.B. a lever for climate protection,” said Mr. Giegold, who sits on the economics committee.

Lagarde Vows to Put Climate Change on the E.C.B.’s Agenda (New York Times, September 4, 2019)

In the lead-up to her confirmation, Lagarde was strident in her remarks about the “strategic review” that would characterize climate change as a “mission critical” consideration for the ECB. Media outlets were eager to attach the “mandate” language, although (as Lagarde herself pointed out in her first post-confirmation press conference) a true formalized mandate would require changes from EU’s Parliament. But that is what narrative does. Once an idea like “let’s do it through a mandate change!” becomes common knowledge, it becomes the default framing for all such stories.

Alas, the cat was already out of the bag anyway. Lagarde’s comments consistently embraced the role of the ECB to selectively do exactly what a mandate would require: influence the composition and winners and losers of the economy by manipulating the price of capital of issuers who fit or do not fit a particular standard.

On the other side of the pond, efforts to drive the Fed into a similar posture in November and December 2019 were relentless from both media and political missionaries. Bloomberg’s coverage, in particular, took a derisive tone on the insistence from Fed officials that playing a role in engineering a solution to climate change was not part of its mandate (“Federal Reserve Leaves Action on Climate Change to Politicians”).

Yet – somehow – the Fed has remained above the fray. For now.

Step 5 | Missionaries warn what will happen if they are not given the power | January 2020

Source: Epsilon Theory, LexisNexis Newsdesk

Step 10 of the Hayek cartoon and Step 5 of our ad hoc alternative framework for a modern path to serfdom cover what happens next: Fear. The primary tool of the Long Now. Don’t mistake me. I’m not talking about fear of climate change, which I happen to think is pretty well-founded. I’m talking about the manufactured, memetic fear of what will happen if we do not consent to transferring the keys to global political power and the world economy over to central banks any more than we already have.

It is almost too perfect that only weeks after Lagarde stepped out of confirmation hearings, the BIS was putting the finishing touches on its new book, entitled “The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the age of climate change.” In context of some of the posturing for more aggressive central banks, it is a pretty measured document and in many places recognizes the fact that this isn’t good metagame. It’s not a fear-mongering book by any stretch. Still, even in its hedging, it can’t help but restate the emerging arguments for an expanded, open-ended role for central banks.

On the one hand, if they sit still and wait for other government agencies to jump into action, they could be exposed to the real risk of not being able to deliver on their mandates of financial and price stability.

The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the age of climate change (BIS, January 2020)

But that’s the whole thing about narrative. It doesn’t matter that the book is measured and cautious about arguing in favor of an expansion of central banking beyond traditional macroprudential activities. It doesn’t matter because a strong narrative means that the media would frame it in a narrative-consistent way. The most shared article referring to that new book? A Forbes article titled “Financial Crisis Sparked by Climate Change Could Leave Central Banks Powerless, Warns New Book.” Fear. Fear of what will happen if you don’t hand over power.

I don’t think we have really seen Step 5 yet. But the language to facilitate it is already floating out there in the ether today, ready for missionaries to seize.

Before we get much further into “OK, so what do we do about all of this”, I think it’s worth remembering a couple things.

First, none of this has a mite to do with what you or I think about climate change. I happen to think it’s almost certain it is happening, and that it is far more likely than not that it is anthropogenic. I think it may be a really big deal economically during our lifetimes. I think many of the things that the people quoted here are talking about are real risks. I think some of them can be mitigated, and should be. You might not, and while my default skepticism about modeling of complex systems means I won’t be as supremely confident as some, I’ll still think you’re probably wrong. But again, that doesn’t matter. Not for anything we are talking about here, anyway.

Second, some of our readers will call me naive, but I think most of these people are well-meaning. Really. The politicians, the media members, the central bankers (okay, maybe not them). This isn’t about evil dictators seeking power.

But it is also worth remembering that nearly every usurpation of the power of the individual – especially already disempowered and disenfranchised individuals – has come in response to really big threats. Real threats. Often, although not always, through well-meaning response to those threats. Literally any argument being made about climate change and its indirect, but potentially significant, relationship to risks to financial markets could have been made historically about all sorts of big, non-financial events of indeterminate probability and hugely variable, potential extreme severity. Disease epidemics, nuclear war, and global conventional wars all fit the bill. What is being discussed here would materially reduce the autonomy and power of the individual in ways for which they have no non-violent avenue for redress.

So what do we do? What can we do?

One thing we can do is ask ourselves, “Why am I reading this now?” Why am I suddenly being told that central banks are a critical pillar to climate change response? Is it because climate change has rapidly emerged from nothingness into the collective zeitgeist in the last year? Is it because we have only conceived the role of green bonds or pricing climate change risk on certain heavily leveraged balance sheets? Really?

Or is it because – like you see elsewhere in the Zeitgeist right now – anger at inaction in the political arena is boiling over? Is it because the impulse to get a man who can make a plan work is becoming irresistible? Do you feel that way? Or, at the least, are you feeling like others want you to feel that way?

As a citizen, another thing I would be looking for right now – what I AM looking for right now – is what all these parties have wittingly or unwittingly set the table for: missionary statements trying to stoke the fear of what will happen if we do not immediately begin granting power to central banks and other similarly unfettered policy-making bodies to take matters into their own hands.

Most importantly, when we see narrative being marshaled to hand over arbitrary power to institutions that are not accountable to us, the people, we can speak up and resist. Resist an extension of the territory granted to central banks beyond traditional, explicitly defined macroprudential activities. Resist extending quantitative easing (and tightening!) to ideologically and environmentally derived rankings of sectors, industries, companies and municipalities.

And when we agree with the underlying aims of those proposing these ideas, we can remind ourselves that it is not less important that we resist them.

It is more important.