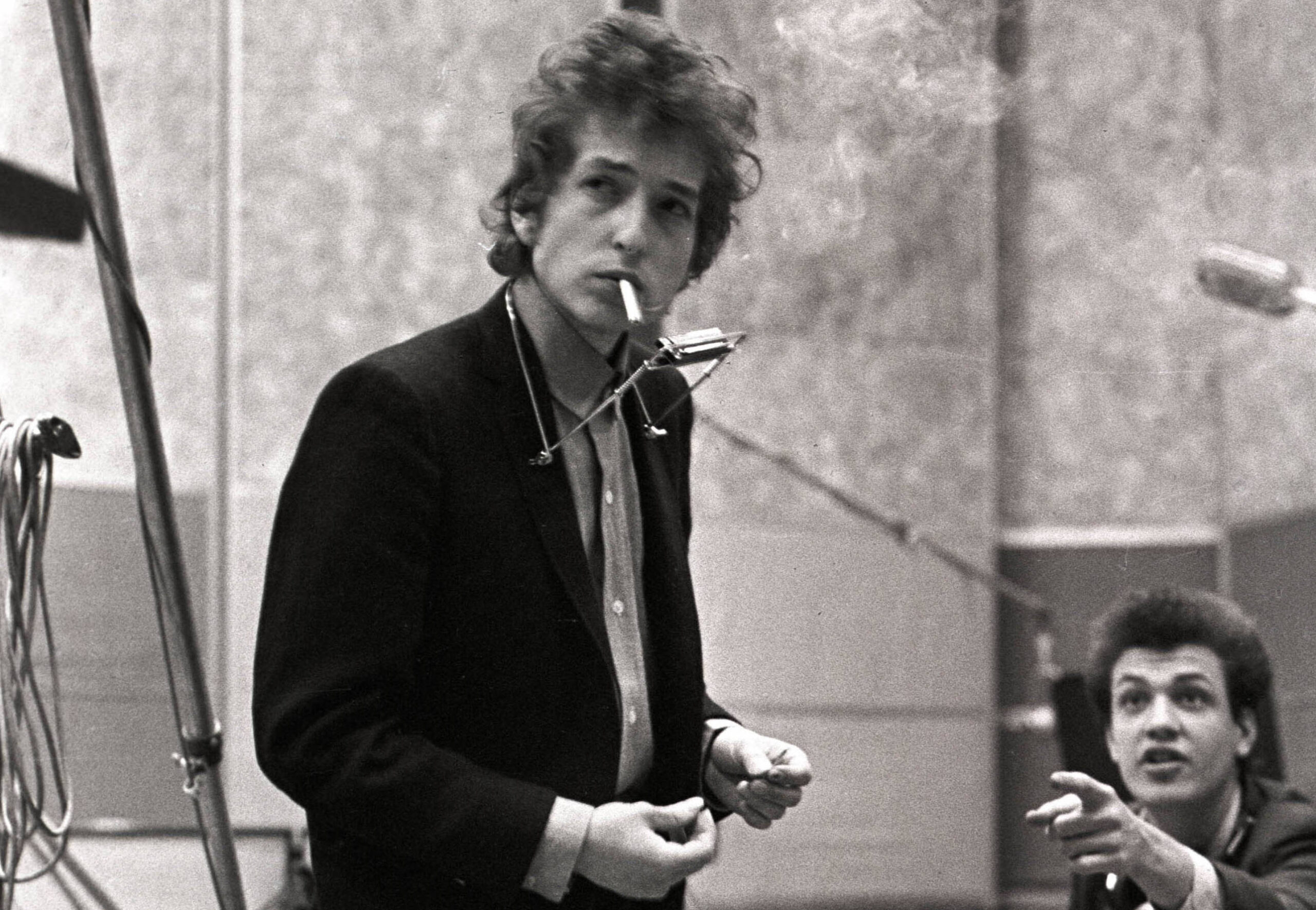

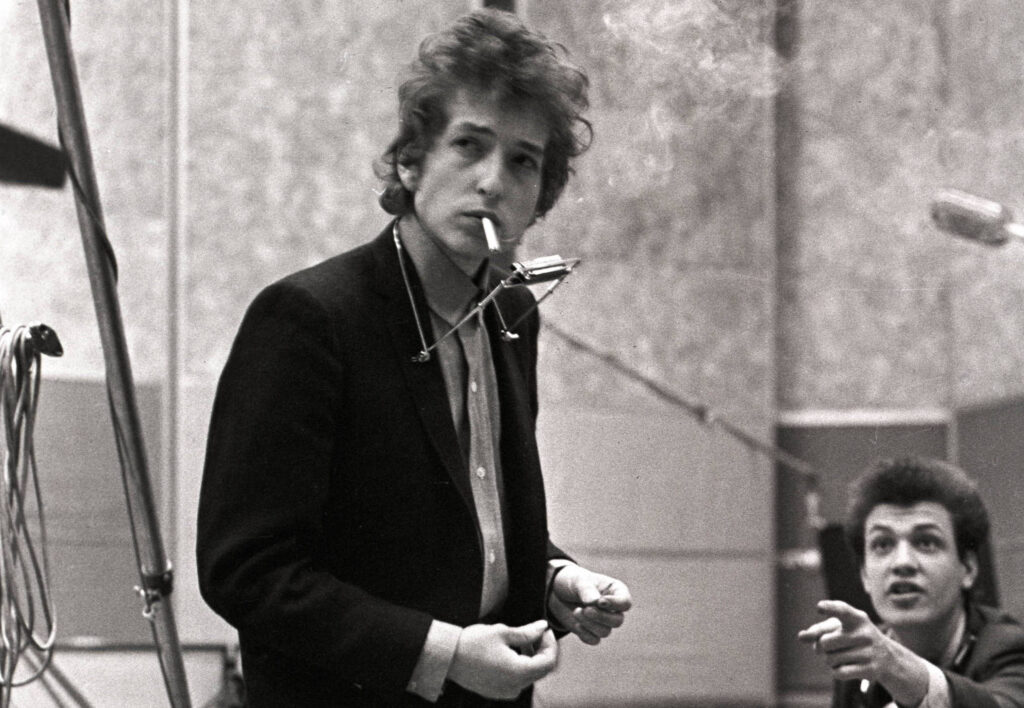

In 1963, Bob Dylan was a fresh-faced kid probably unrecognizable to most Americans, but he showed he was already an old soul when he delivered a speech in the Grand Ballroom of New York City’s American Hotel that December.

It was about two weeks before Christmas, and Dylan was on hand to receive the Tom Paine Award, bestowed annually by the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee to honor individuals for service in the fight for civil liberty.

It was a period of change, and Dylan had risen to fame in large part because of his protest songs of the period—such as the 1962 hit “Blowin’ in the Wind”—that touched on themes related to the civil rights and anti-war movements.

Dylan’s address that night was not what America was expecting, however. In a short, rambling, unscripted monologue, the young folk singer touched on Woody Guthrie, Lee Harvey Oswald, race, baldness, and the strange gifts he received from fans. Dylan even suggested that the young people in the audience would be better off somewhere else.

“I’m proud that I’m young. And I only wish that all you people who are sitting out here today or tonight weren’t here,” said Dylan. “Because you people should be at the beach. You should be out there and you should be swimming and you should be just relaxing in the time you have to relax.”

Many have written about Dylan’s speech that night—including Dylan himself, who days later penned a poetic explanation attempting to explain his thought process and the tumult of feelings he was experiencing.

Whatever intent lay behind his words, the award speech is generally seen as the first signs of Dylan’s disillusionment with the 1960s folk protest movement. The following year, in a wide-ranging interview with Nat Hentoff published in The New Yorker, Dylan explained that he was done with “finger-pointing” songs.

“Those records I’ve already made, I’ll stand behind them, but some of that was jumping into the scene to be heard and a lot of it was because I didn’t see anybody else doing that kind of thing,” Dylan told Hentoff. “Now a lot of people are doing finger-pointing songs. You know—pointing to all the things that are wrong. Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know—be a spokesman.”

Dylan didn’t stop there, however. Ever the artist, he expressed his disenchantment in one of the last songs he recorded for his 1964 album Another Side of Bob Dylan: “My Back Pages.”

A lovely but mournful tune, “My Back Pages” is a coming of age song that expressed doubts about the songwriter’s earlier zeal. Historians say the song left many diehard Dylan fans confused and even horrified for its seeming refutation of the Jester’s earlier protest ballads.

“No song on Another Side distressed Dylan’s friends in the movement more than ‘My Back Pages’ in which he transmutes the rude incoherence of his ECLC rant into the organized density of art,” author Mike Marqusee writes in Chimes of Freedom. “The lilting refrain … must be one of the most lyrical expressions of political apostasy ever penned. It is a recantation, in every sense of the word.”

Below are the lyrics to “My Back Pages,” which readers can analyze for themselves. (After reading the lyrics, check out the live performance of “My Back Pages” Dylan performed with music legends Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Tom Petty, Neil Young, and Roger McGuinn of the Byrds at the 30th Anniversary Concert in Madison Square Garden in 1994.)

Crimson flames tied through my ears, rollin’ high and mighty traps

Pounced with fire on flaming roads using ideas as my maps

“We’ll meet on edges, soon, ” said I, proud ‘neath heated brow

Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now

Half-wracked prejudice leaped forth, “rip down all hate,” I screamed

Lies that life is black and white spoke from my skull, I dreamed

Romantic facts of musketeers foundationed deep, somehow

Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now

Girls’ faces formed the forward path from phony jealousy

To memorizing politics of ancient history

Flung down by corpse evangelists, unthought of, though somehow

Ah, but I was so much older then. I’m younger than that now

A self-ordained professor’s tongue too serious to fool

Spouted out that liberty is just equality in school

“Equality,” I spoke the word as if a wedding vow

Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now

In a soldier’s stance, I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach

Fearing not that I’d become my enemy in the instant that I preach

My existence led by confusion boats, mutiny from stern to bow

Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now

Yes, my guard stood hard when abstract threats too noble to neglect

Deceived me into thinking I had something to protect

Good and bad, I define these terms quite clear, no doubt, somehow

Ah, but I was so much older then I’m younger than that now

Dissecting art to harvest meaning is a tricky business, but there’s little doubt that “My Back Pages” is a reflection on Dylan’s earlier protest songs.

The lyrics suggest the young songwriter had changed or grown in some way. That he’d become aware of his own “half-wracked prejudice” that caused him to scream “rip down all hate.” That liberty and equality are perhaps not what he thought. That the world actually might be gray, and claims that it is “black and white” are “lies.”

The tune’s wonderful refrain—”Ah, but I was so much older then/I’m younger than that now”—is not a senseless paradox but a reflection of a similar idea. It suggests that the young songwriter had obtained the Socratic wisdom that true knowledge is realized by grasping how little we truly know.

This is not to say Dylan had doubts about the causes he championed. He makes it clear in interviews that he did not. What he appears to have opposed was the lack of individualism he saw in the mass protest movement.

“I am sick so sick at hearin ‘we all share the blame’ for every church bombing, gun battle, mine disaster, poverty explosion, an president killing that comes about,” Dylan wrote following his speech. “it is so easy t say ‘we’ an bow our heads together I must say ‘I’ alone an bow my head alone for it is I alone who is livin my life.”

While Dylan appeared uncomfortable with the idea of collective guilt (an idea on the rise today), his ECLC speech reveals he saw individuals capable of great evil. In perhaps the most bizarre part of the address, Dylan compared himself to Lee Harvey Oswald, who the previous month had assassinated John F. Kennedy.

“I have to be to be honest, I just got to be, as I got to admit that the man who shot President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, I don’t know exactly where—what he thought he was doing, but I got to admit honestly that I too—I saw some of myself in him,” Dylan said. “I don’t think it would have gone—I don’t think it could go that far. But I got to stand up and say I saw things that he felt, in me.”

Dylan was self-aware and honest enough to recognize that hate can consume even the best of us. In a moment of candor in an unscripted speech, he shared an apparent realization: that within himself he recognized the seed of the same righteous anger that sparked assassinations, wars, and turmoil.

To be sure, there’s nothing inherently wrong with protesting. Few would deny that many issues in America—in the 1960s and today—are worthy of protest.

And yet much of the protesting we see today looks much like the “half-wracked prejudice” described by Dylan. Many protesters seem bent on tearing down every symbol that offends them, whether it be a monument to Christopher Columbus, George Washington, US Grant, or Thomas Jefferson. We see protesters physically taking control of a portion of a major US city and making demands. We see rioters attacking innocent people in streets and burning businesses that sustain our communities.

Injustice has always existed and always will. There is nothing wrong with seeking to make the world a better place, but we should remember that moral righteousness divorced from self-awareness, humility, and empathy for political adversaries can lead to the same fanaticism that tore France apart in 1789 and China in the 1960s.

The danger is that in our righteous zeal we might come to believe we possess the knowledge and ability to shape the world in our own image, never realizing that each of us carries the potential to do evil as well as good.

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart,” Solzhenitsyn wrote in his masterpiece The Gulag Archipelago. “And even in the best of all hearts, there remains…an uprooted small corner of evil.”

Fifteen years before publication of Solzhenitsyn’s most famous work, a 22-year-old Bob Dylan appears to have gleaned this startling truth about good and evil.

Young people today would do well to emulate Dylan, who as a young man remained faithful to his ideals but made a conscious decision to reject inhumane zealotry.