Authored by Jan Jekielek and Irene Luo via The Epoch Times,

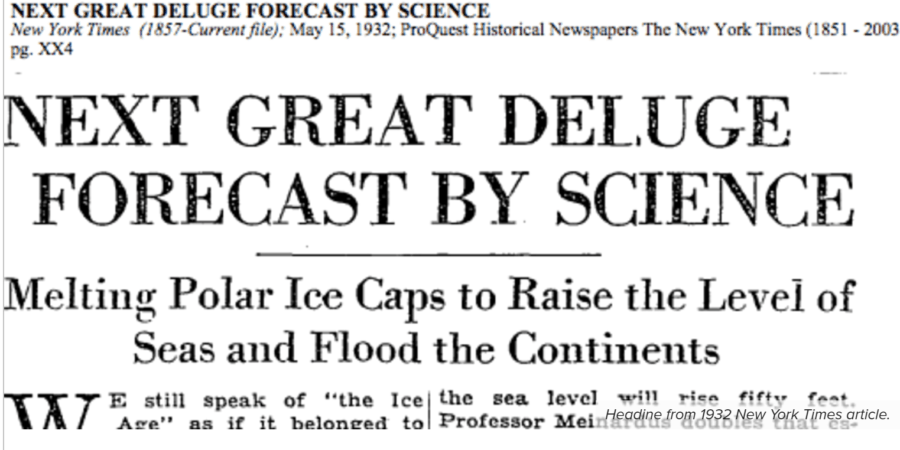

For years, experts have predicted impending catastrophe from climate change. Thirty-one years ago, a senior U.N. environmental official told the Associated Press that governments had only a 10-year window to reverse global warming before it went beyond human control.

Like many others, Michael Shellenberger feared climate change was an existential threat to human civilization. He has devoted three decades of his life to environmental activism and improving the lives of people in poor or developing nations. At age 16, he threw a fundraiser for Rainforest Action Network. He’s fought to protect redwood trees in California, traveled to the Congo to study the impact of wood fuel use on gorillas, sought better working conditions for factory workers in Asia, and pushed the U.S. government to fund renewable energy.

Now, he believes the climate movement is radical, alarmist, and causing anxiety and depression, especially among young people. One in five British children say they’ve had nightmares about it, according to a large national survey earlier this year.

Although global temperatures are rising and humans are a major contributor, that doesn’t mean the world is ending, Shellenberger argues in his new book, “Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All.”

Contrary to what media headlines would suggest, climate change hasn’t made natural disasters worse. Fires, for instance, have declined 25 percent around the world from 1998 to 2015. And in California and Australia, where fires have increased, the biggest contributing factors were humans allowing wood fuel to build up and constructing homes near forests—not climate change.

Claims of crop failure are similarly exaggerated, in his view. Humans already grow enough food for 10 billion people, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) predict crop yields will continue increasing.

Global sea levels are rising, but Shellenberger believes humans can adapt in the decades to come. The Netherlands managed to become a wealthy nation while adapting to having one-third of its landmass below sea level. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates sea levels could rise 2.7 feet by 2100; some areas of the Netherlands are as low as 20 feet below sea level.

To Shellenberger, climate alarmism is creating more problems than it solves. It’s excluding viable solutions such as nuclear energy, preventing desperately needed development in impoverished nations, and diverting attention away from serious environmental problems, like overfishing.

Wind and Solar Aren’t the Future

In 2003, Shellenberger co-founded a “New Apollo project,” a predecessor to the Green New Deal, to direct taxpayer money to renewable energy.

“What I didn’t realize—and I think most people don’t realize—is just how much land it would require,” Shellenberger said, in an interview with The Epoch Times’ American Thought Leaders program.

It takes about three to four hundred times more land on average for a wind farm or solar farm to generate the same amount of electricity as a nuclear power plant or a natural gas plant, Shellenberger said.

As Shellenberger writes in “Apocalypse Never”:

“If the United States were to try to generate all of the energy it uses with renewables, 25 percent to 50 percent of all land in the United States would be required. By contrast, today’s energy system requires just 0.5 percent of land in the United States.”

Solar and wind are fundamentally inefficient and costly ways to produce energy. “They are unreliable, thus requiring 100 percent backup, and energy-dilute, thus requiring extensive land, transmission lines, and mining,” he writes.

Wind farms are also devastating to endangered species of birds, bats, and insects, especially when the wind farms are located on their migratory paths. Wind turbines especially threaten large, endangered species like hawks, eagles, owls, and condors.

Shellenberger told The Epoch Times, “I always joke, there’s nobody that’s more alienated from the natural world than environmentalists.”

If carbon emissions will have the catastrophic consequences that activists claim, it doesn’t make sense to rule out the most obvious solution—nuclear. In 2017, Sweden was already generating 95 percent of its total electricity from sources that don’t emit carbon, mostly nuclear and hydroelectric power, Shellenberger said.

In contrast, Germany will have spent $580 billion by 2025 to make the switch to renewables, according to Bloomberg. But only 34 percent of Germany’s electricity is generated from wind and solar.

Following the highly publicized nuclear power plant disasters in Chernobyl and Fukushima, many fear nuclear power and potential radiation, but these fears are largely misplaced, in Shellenberger’s view.

According to the United Nations, only 50 deaths can be directly attributable to Chernobyl. Five thousand cases of thyroid cancer are linked to radiation from the disaster, but thyroid cancer is highly treatable, with a death rate of 0.5 percent.

In Fukushima, radiation levels were so low, that there have been no known deaths from radiation exposure, Shellenberger noted.

Nuclear has a very small known death toll. Meanwhile, air pollution causes an estimated 7 million people to die worldwide every year, according to the World Health Organization.

As for nuclear waste, nuclear produces little waste relative to other forms of energy. It produces 200 to 300 times less waste than solar energy. And the waste—namely the used nuclear fuel rods—are safely contained, whereas the waste that comes from coal, natural gas, and solar panels go into the environment.

For Shellenberger, energy sources sit on a spectrum, from low to high density. “So we go from wood and dung to coal and hydroelectric plants to petroleum to natural gas to uranium,” Shellenberger said.

The higher the energy density the more efficient the source is, the less harm it does to the environment, and the less carbon it emits.

“I can cook a pot of beans with a lump of wood; I might be able to heat my house for 24 hours with a lump of coal; and with a lump of uranium, I can power my entire high-energy life.”

“If the people who are proposing to ban fracking were similarly proposing to build a lot of nuclear power plants, that might be an interesting idea. Mostly though they’re not,” Shellenberger said.

Shellenberger said the United States should follow in the footsteps of other nations rich in natural gas, such as Russia and the United Arab Emirates. “You build nuclear power plants to replace the natural gas you’re burning for electricity at home. And then you export your natural gas abroad,” Shellenberger said. This boosts America’s exports and also helps countries make the shift from coal to natural gas, a win for the environment.

Crippled Development

Many rich countries today, as a result of the climate movement, are no longer seeking to eradicate poverty, but instead trying to make poverty “sustainable,” according to Shellenberger.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, “the World Bank and other international development banks would finance the infrastructure of economic development in poor countries, which is mostly roads, hydroelectric dams, flood control, electric grids, sewage systems,” Shellenberger said.

But “after apocalyptic environmentalists exercised their influence over the World Bank, the World Bank now doesn’t fund development, it funds charitable activities. So instead of funding modern agriculture with irrigation, tractors, fertilizer, it now funds agroecology and other things to basically keep people on the farm,” Shellenberger said.

Yet, development is also precisely what helps nations deal with the adverse effects of climate change.

And the World Bank now focuses money on solar and wind instead of hydroelectricity, natural gas, and nuclear. The European Investment Bank has announced it would stop funding fossil fuel projects by 2020.

Shellenberger argues in his book:

“It is hypocritical and unethical to demand that poor nations follow a more expensive and thus slower path to prosperity than the West followed.”

“As we have seen, there is no energy leapfrogging…There is no rich low-energy nation just as there is no poor high-energy one,” Shellenberger writes.

Failures to finance development also threatens national security in America and Europe, Shellenberger said. “If the West isn’t going to finance the roads and power plants and stadiums and all the things of development in Africa and Asia and Latin America, it’s being financed by China,” Shellenberger said. And “China’s not interested in freedom and democracy.”

Overshadowed Environmental Problems

There are “serious environmental problems that we don’t pay enough attention to because we’re so wrapped up in our own personal apocalyptic drama,” Shellenberger said.

Animal populations are declining not because of climate change, but because of tropical deforestation. People in developing countries still rely on charcoal and biomass for fuel. The solution is to help people get access to liquefied petroleum gas and cheap electricity, Shellenberger argued.

Besides shrinking habitats, one of the biggest threats to wild animals “is just that we still eat a lot of them,” Shellenberger said. Overfishing endangers wild fish species as well as the whales and sea animals that rely on them to survive.

“Many environmental groups—because they have this romanticization of nature and harmonizing with nature—have actually condemned farmed fishing. Farmed fish is how we save wild fish,” Shellenberger said.

And while media reporting has highlighted how sea animals, especially sea turtles, are ingesting potentially deadly plastic waste, it’s also true that sunlight breaks down most plastic on the ocean’s surface.

The best way to minimize plastic waste in the ocean isn’t banning plastic straws and plastic bags but to help poor or developing countries build a strong waste collection and management system, Shellenberger argues. One study found that five countries in Asia—China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka—contribute half of the world’s mismanaged plastic waste.

To Shellenberger, the modern-day climate movement is driven by a secular quasi-religion.

“People should distrust what they hear about what saving the environment requires because so many of the people that are telling you things are in the grip of a religion, rather than paying attention to what the science says,” Shellenberger said.